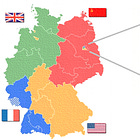

Berlin gained significance in the Cold War as tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States played out throughout the world. In the eyes of the West, Berlin became an outpost of freedom and an island of democracy in a deep red sea of Communism. For the Soviets, it became an arena where they could showcase the fruits of Communism. Both sides faced struggles, attempted to reduce crime, and constructed narratives about cinema and its effects on young people to reaffirm their systems. Despite sharing similar concerns, their discourse about the impact of cinema on the youth served to contrast their socio-political systems.

The Perils of American Film and Culture

During the Cold War, both East and West Germany faced crime and dealt with dissatisfied youth. State officials in both Germanies were concerned about the negative ways in which American film was affecting the German youth (Poiger, 2009). Statesmen in both, worried that West Berlin theaters brought Western youth culture into the East (Poiger, 2009). Young East Germans often went to West Berlin cinemas before the Wall was built. As the wall was being built, there were stories of wall crossings with the sole purpose of watching films (Berger, 1956). Even after the construction of the Wall, there appears to have been a group of young East German wall jumpers that made it to West Berlin and back, just to see a film.

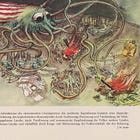

Capitalists Only Care About Profits, Even if it Turns Young People into Criminals

In the East, the connection between culture and behavior continued to worry leaders who linked capitalism to uncleanliness and vacuous values, in contrast to the “spiritual goods” offered in the East (Berger, 1956). They expressed concern about the effects of this industry on the development of cultural values and attitudes that were compatible with the socialist way of life. An article in the Eastern press criticized Western cinemas close to the border as unclean and said they had “dirty air inside” because there was “no time to clean between showings” so they could maximize profits (Berger, 1956). Even worse, from an Eastern perspective, these cinemas operated without any concern for the negative ways in which their products drove young people to behave in undesirable and unacceptable ways.

Eastern critics argued that the films celebrated antisocial attitudes and behaviors. Officials feared that the movies could lure and trick young socialists. Similarly, when East Germans fled to the West or rioted in 1953, Eastern authorities would claim that these people were tempted and misled by Westerners. The depiction of socialized citizens is strange, for they are terrifyingly vulnerable to outside corruption.

The Soviets accused American films of encouraging violence and upheaval, reiterating their belief in the power of culture to shape behavior. In 1955, a film review accused the film The Wild Ones of causing unruliness and gender upheaval (Poiger, 2009). Implying that socialism is hard and, to some extent, contrary to man’s nature. Thus, there is a need for a totalitarian state that allegedly acts like a parent.

Alice Settiner (1950) linked these films to a series of violent crimes worldwide in an article for Neues Deutschland. She wrote about a child who murdered an older woman in Gladow so he could get money to see a film. She attributed the act to the “corrupting influence of gangster pulp fiction,” making both the culprit and the woman victims (Settiner, 1950). Victims to profit-making and the subjugation of all that matters to greed. In this way, East German authorities hoped their criticism of fascism would resonate.

Settiner argued that American films’ corrupting influence was evident worldwide. She claimed that there are a “host of similar cases of youthful murderers and criminals” which “are part of the same phenomenon” (Settiner, 1950). She cited an American Senator who claimed that these films were “an education” for those seeking to commit “perfect murderers” (Settiner, 1950). There are two conclusions that readers could have drawn from this. One is that the Senator has admitted that the US was intentionally creating media that trained young people to commit murder and numbed them to violence. More likely, readers would have concluded that these films were eroding values and driving young people to murder and a series of other crimes.

Settiner made a multilayered criticism of capitalism by using an American Senator's words to support her case. She implied that even Americans recognized the pernicious effects of their propaganda, and they were still making these films, thus hinting that capitalist systems prioritize profit over human life. Secondly, it suggested that capitalism cannot solve social problems even if it is able to identify them.

The Importance of Material Conditions

Commentators in the East continued to stress the power of the environment to shape behavior and linked Western influences to undesirable behaviors. Settiner claimed that these films had transformed the United States into a land riddled with crime and children who murder (Settiner, 1950). The Soviets claimed that the “rubbish” crime stories depicted in films and serials corrupted the youth. Settiner told the story of a young child who took his father’s gun and killed someone. The child later claimed he got the idea from reading comics (Settiner, 1950). In short, children cannot resist the lure of these films, and the stories and images they depict corrupt their understanding and, hence, their actions. Settiner concluded that American media is nothing but a

“conscious and systematic education to brutality, to disregard for human life, to indifference toward injustice and despotism, a systematic education to inhumanity, in short, the ideological preparation for a new madness of war” (Settiner, 1950).

Settiner’s review of The Wild One exemplifies how the East tried to highlight the superiority of its socio-political system.

The problem with American popular culture is that it interfered with the development of the youth, turning otherwise good young socialists into people who protest, riot, and kill. From the Eastern perspective, American popular culture had displaced Nazism and Hitlerism as the root cause of youth crime (Evans, 2018). In 1958, a Soviet memo argued that better educational interventions would reduce youth crime (Evans, 2018).

Films Corrupt (Sometimes), But They Are Not the Problem

Western commentators were aware of the critiques coming from the East. Werner Berger argued that there was no need to “address the sanctimonious arguments by the Eastern press, which claims that young people were being enticed to commit criminal acts by the films (Berger, 1956). In the West, the impact of American popular culture was contested between those who rejected the Eastern perspective and those who worried about films' effects on young Germans. Despite sharing similar concerns as their Eastern counterparts, Western commentators and officials did not link any of these problems to capitalism.

In 1956, Adolf Busemann wrote an article expressing his worries about youth crime. He was also preoccupied with the effects of films on young people, which he linked to the kinds of crimes young people were committing. He described a gang involved in eighty-one break-ins over six months, composed of nine to fourteen-year-olds. Their leader claimed to be inspired by Westerns (Busemann, 1956). In West Germany, the crimes of the young had often been linked to broken homes, but in this case, most of these children came from “respectable families,” suggesting no one was immune to the pernicious effect these films could have (Busemann, 1956).

Western commentators often claimed that the deterioration of values explained the problems of young Germans. Franz-Josef, the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, argued that mothers needed to teach their children values and thus “take the place of all television sets, cars, radio photographs, and trips abroad” (Wuerling, 1963). Even respectable families may have mothers who are derelict in their duties. Films and values are not necessarily products of capitalism.

Western thinkers considered the environment essential in shaping behavior. Berger raised the possibility of other cultural or socio-economic conditions in East Berlin that can account for their crimes. Others like Walter Abendroth, a cultural critic, thought that it was the situation in which the youth found itself that drove them to act in undesirable ways (1956).

The Importance of the Environment

These West German commentators also suggested that the environment caused undesirable behaviors, but the causes were not linked to capitalism.

Abendroth argued that young people commit crimes because of the world adults had built for them (1956). He wrote an article about the influence of movies for Die Zeit, a West German periodical. In his article, he recognized that there had been many murders in the US and the UK, which demanded an explanation (Abendroth, 1956). He thought that these murders could be linked to film and fanaticism. Nevertheless, such a link did not imply causation. Abendroth maintained that “there would be no youth problem if adults did not create a problematic world for the youth!” (1956) This is not a claim that capitalism or the pursuit of profit creates such problematic worlds but that adults had structured their world incorrectly.

Abendroth hypothesized that youth crime was a cultural problem that could be solved within a capitalist system. He posited that everyone has a religious impulse that can never be “cast off,” but that can be unleashed in a “perverted form” (1956). He also mentioned Hitler to demonstrate the frenzy this religious fervor can take. He contended that the “loss of faith produces superstitions to the same degree” and that the vacuum this creates demands to be filled (Abendroth, 1956). Therefore, he argued that both Hitler and American popular culture were perversions of that religious impulse and that the “orgies of jazz fans” could lead to a state of consignation and “recklessness” where people could behave terribly (Abendroth, 1956). Thus, he suggested that the behavior of rock and roll enthusiasts is similar to those who supported the Nazis (Abendroth, 1956). He thought these concerning behaviors resulted from the fact that people had ignored spiritual goods.

Abendroth’s proposed solutions to the problem of youth crime implied they could only be achieved in the West. He prescribed a strong humanist education to reduce the “indiscriminate hunt for autographs” (Abendroth, 1956). Abendroth’s concerns were less about the specific effects of American popular culture but about its ability to fill the void left by lack of faith. His advocacy for humanist education and more religion are both compatible with capitalist systems.

In general, Western commentators were concerned about how films impacted young Germans. They recognized that young Germans were misbehaving and engaging in criminal activity. They accepted the conditions in which these behaviors occurred arose in a capitalist society. However, these problems were neither linked to this socio-economic system nor presented as inherent products of capitalism. Given socialism's opposition to religious systems, Abendroth's prescription of humanism or religion meant that this problem could only be solved within a capitalist system. West Germans who worried about the influence of films often implied that these effects would be worse in a socialist system. Others in Western Germany worried that the movies spurred the Halbstarke movement. Concerns about the Halbstarke grew in 1955 when the noisiness and skinny dipping by members of a gang that called itself the Wild Ones convinced many of the pernicious influence American film had on the young (Poiger, 2009).

Conclusions: A Cold War with Many Fronts

East and West German thinkers worried about the influence of film on their young citizens. Commentators on both sides argued that the environment affected how young people behaved and that films were setting a bad example. In the East, concerns about cinema were often tied to capitalism and their ideas about what drives people's behavior.

East German critics’ perspective reveal interesting assumptions worth fleshing out. Their worldview takes for granted that people are like putty and external influences (like film, radio, music) can radically change how they behave. From this perspective, it is easy to see threats everywhere because exposing people to certain films could make them engage in antisocial behavior. Thus, if a state wants to protect people, it must exert stringent control over the kinds of media that those people consume. Crucially, this interpretative step also allows them to claim ethical superiority over the West because a Socialist regime would never allow such films to be made, knowing that they jeopardize the health of their people. In contrast, they claimed capitalism sacrificed its people for profit making.

West German concerns over American films reveal different worries about the state of affairs. They were largely concerned about meeting the needs of young people and thought that the youth was misbehaving because the State had failed them. They found fault with structural factors, physiological issues, and a lack of moral education. Thus, the nefarious effects of the films only exist because of these other failures.

The different ways these States understood the world drove how they interpreted these films and their alleged effects.

The Cold War had many fronts, and given the absence of direct confrontation, every other front was significant. We recognize proxy wars, which we have intentionally ignored to highlight other less tangible fronts on which the Cold War was fought. We suspect that plenty of these interpretations and commentary were deliberately weaponized to attack the Other’s socio-political system. Nevertheless, these worldviews were totalizing, and thus, even if specific critiques were propagandistic, we suggest that they still reveal how historical actors understood their worlds. More importantly, efforts to address the problems of youth crime and the effects of the cinema were designed following each side’s interpretative frameworks.

This post heavily draws from an essay Christian wrote for a class on the history of everyday life in Cold War Berlin. Christian would like to express his gratitude to Briana and Caroline for an exciting course, their help and support. Lucas and Christian have worked on a substantial revision of Christian’s original work.

If you liked this story and want to learn more about Crime in Cold War Berlin, we urge you to read:

West German thinkers argued that social factors drove youth crime. These were said to be much worse in East Germany.

Western Description of Youth Crime Implied Capitalism was Better than Communism

A discussion of how East German Criminologists Claimed Capitalism made people worse

East German Criminology Linked Fascism, Capitalism, and Crime

The terrible condition in which Berlin found itself after the war

Ideas about Crime in Weimar Germany and Nazi Germany

Another terrific article full of ideas. Th question of whether film convinced people to commit crime is in part a psychological one, of course, so I read some of this unfamiliar material with particular interest.

Thank you!