East German Criminologists Claimed Western Influences Caused Crime

Soviet ideology shaped how East Germans Interpreted Undesired Events

During the Cold War, East and West German explanations regarding why people committed crimes highlighted the differences between their socio-political systems*. The Americans and the Soviets administered their occupation zones and developed interventions to solve their respective issues. As the Cold War intensified, the outcome of each of their zones gained significance because it allowed others to compare communism and capitalism.

Both East and West Germany sought to combat crime because it threatened stability and order. Their respective thinkers focused on similar factors such as structural damage, broken families, broken society to explain why people commit crimes. In this article we explore how the East German Regime (GDR) weaponized crime related discourse to condemn fascism, capitalism, and the West.

After the war, there was an increase in crime throughout Germany. The Weimar/Nazi view that criminality is biologically determined, could not fully account for such a dramatic increase in crime. The people in Berlin had not changed, but the amount of crime continued to increase. Thus, the only acceptable explanation was that the conditions had pushed people, who would otherwise be law-abiding citizens, to commit crimes. East Germans concocted explanations that suggested capitalism was corrupt and destructive.

Beginnings: Capitalism & Fascism Are Intertwined

Initially, Soviet commentators argued that factors which increased criminal activity were linked to Nazism. In June 1945, the German Central Committee, issued a proclamation where they blamed “unscrupulous exploiters” for supporting Hitler and the war because they wanted to “make a killing” (PPC Proclamation, 1945). The conditions that led to the increase in crime were therefore linked to traits directly connected to capitalism such as exploitation and putting profit over ideas and people. The proclamation implied that without these, there would have been no Hitler, and without Hitler, no war and hence no increase in crime.

Moreover, it was the drive for profit which made Germans forgo their “most basic sense of decency and justice” (PPC Proclamation, 1945). And for what did Germans sacrifice these most important values? For the promise of a “well-laid lunch and dinner table” (PPC Proclamation, 1945). The Central Committee declaration implied that capitalism erodes the human spirit and resulted in a tragic war which they claim, was caused by structural factors. The missing children, the bombed cities, the dead Germans are thus, in their view, a direct product of the drive to exploit which capitalism engenders.

The Social Unity Party linked the increase in crime to Hitler, which allowed them to stress the importance of material relations and thus highlight the dangers of capitalism. In a statement written by Paul Verner, a party official, the party claimed that the challenging situation in which a future that seems “nebulous and a long way off” contributes to the growth in crime (Verner, 1946). The statement proclaimed that this increase in youth crime “is a direct result of the Hitler's education and the war requires no proof” (Verner, 1945). These are all social or cultural explanations for the increase in crime. Given the Soviet ambitions to turn Germany into a Socialist nation adopting a more biologically deterministic view, would render the transformation impossible. Secondly, Marxism presupposes that material conditions determine consciousness.

In fact, Verner explicitly predicted a decline in youth crime in relation to the improvement of living conditions (Verner, 1946). Thus, there is an explicit connection between material conditions and criminal activity. Yet, this improvement cannot be accomplished via capitalism because that system erodes the values necessary to prevent exploitation. Both Verner and the proclamation claimed that capitalist greed and its structures led and empowered Nazism, thus, subsequent improvements need to be produced through different mechanisms. Soviet criticisms of American actions would echo this critique.

These statements use the increase in crime to highlight the different effects of capitalism-fascism and socialism on the young. Verner wrote that “nothing would be more mistaken” than to conclude that the “youth is morally dissolute” from the increase in youth crime (Verner, 1946). Likewise, the proclamation denounced the “sensationalism and the sinister intentions of reactionary circles” who blamed the youth and tried to cover “the real causes” (Proclamation, 1945). Implied in this statement is a claim to understand and hence address the real causes rather than obfuscate them.

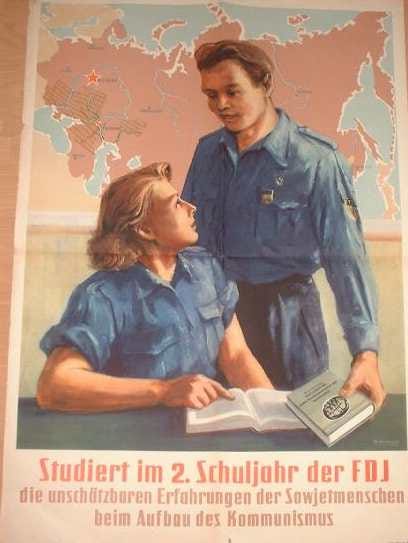

Both documents argued that German youths are committing crimes because their society was improperly organized. The way it was organized led to Nazism, and it eroded essential values by promising material goods (Proclamation, 1945). Given the importance they gave to social influence, the East proposed a break with the punitive measures of the past and aimed to reform young offenders into good socialists (Evans, 2018). The solution to the problem of youth crime was perceived to be giving the youth a “new spirit.”. Thus, the Soviets create youth centers to give troubled youth the skills to be good socialists.

Raising Good Socialists & Youth Crime

Making good socialists required sending troubled youths to special centers where they could be taught productive skills and given a new spirit. In East Germany, the sex of young criminal offenders also determined how they were treated. Their sex affected whether certain behaviors were seen as criminal, deviant, or not. The Soviets expunged discussions of biological determinism from what they considered to be criminal acts; however, the list of deviant acts remained essentially unchanged (Evans, 2018).

Young “criminal” women were first taken to another place where they were tested for venereal diseases and were often sequestered while receiving treatment (Evans, 2018). In contrast to discussions about young wayward women, the question of abortion in East Germany shows a more progressive view. In August 1945, abortion was legalized in cases it resulted from a crime (Gutenberg, 1946). Perhaps this was a response to the many rapes committed by Soviet soldiers. At a meeting of gynecologists, Gutenberg recognized that the law may be abused by people who did not want children, that it was imperative to preserve “the fundamental right to demand the termination of pregnancy” (Gutenberg, 1946). In the East, it was even suggested that women should be able to abort because of “social hardship”, which the Bishop of Thuringia strongly opposed (Jürgen, 1945). The discussions about abortion suggest an underlying problem of rape.

On the other hand, men were interviewed and efforts were made to determine why they had committed those crimes. These reasons were often said to be their environment or their broken families rather than some preexisting disposition to criminality (Evans, 2018). This focus on social causes echoes the rhetoric of the proclamation which linked economic structures in Germany to fascism (Proclamation, 1945). One of the implications of this analysis is: once the material conditions change, once the means and modes of production are socialized then people should change their behavior. In the case of young women, criminologists worried about their future reproductive behaviors whereas in the case of young men the focus was their future productivity (Evans, 2018). Thus, rather than inculcating some revolutionary way of life, Eastern institutions were reifying traditional gender roles (Evans, 2018).

Eastern efforts to combat crime through detention centers often fell short of what they aimed for. These detention centers were often counterproductive as young people learnt the skills they were intended to learn, but also shared knowledge about how to commit crimes (Evans, 2018). The government in Berlin created a center where young people who committed crimes were sent to be processed. This had to be relocated because tens of thousands youths had passed through by 1948 (Evans, 2018).

The creation of these institutions and their efforts to educate and reform former young criminals shows these efforts were closely associated with “building socialism through (re)productive labor” (Eisenhuth & Krause, 2014). The transformative power of labor reiterates how important Soviets thought the social environment, and especially labor was in shaping behavior. The Soviet treatment of youth offenders influenced their policies towards young criminals during the time where they repudiated the Nazi past, developed a new socialist nation, and tried to legitimize their regime (Evans. 2018).

Outcomes

These views and analytical tools shaped how East German authorities used discourses about crime to condemn capitalism and fascism and highlight the benefits of socialism. In our next post we shall delve into narratives about the massive 1953 protests, the Billy Halley concert, and the rebellious Halbstarke.

This post heavily draws from an essay Christian wrote for a class on the history of everyday life in Cold War Berlin. Christian would like to express his gratitude to Briana and Caroline for an exciting course, their help and support. Lucas and Christian have worked on a substantial revision of Christian’s original work.

Sources

'The Weimar/Nazi view that criminality is biologically determined, could not fully account for such a dramatic increase in crime. The people in Berlin had not changed, but the amount of crime continued to increase.' This is an important point. Since its more or less impossible to carry out structured formal research (such as experiments) into the causes of crime, it seems vital to learn from history and its quasi-experiments. The implication here is certainly that social conditions had some sort of effect. The same argument can be made in reverse for Australia: a nation largely populated by the descendants of criminals, which manages to be one of the most law-abiding nations on Earth.