East Germany, Crime & the "dehumanizing effects" of capitalism.

Turning Good People into Raging Beasts.

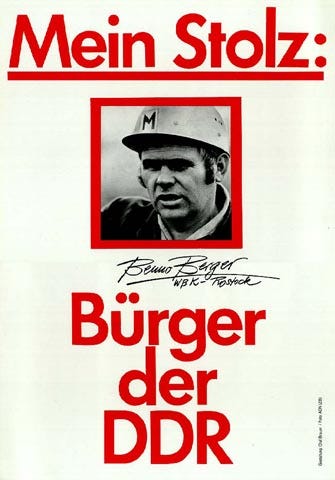

During the Cold War East Germany offered an analysis of criminality that allowed it to condemn capitalism. During the early 1950’s, most crimes in the East would be described as crimes against social property (Reuter, 1992). In 1952, Walter Ulbricht would point to the West and blame their desire to make Germany into a battleground for many of the problems that they currently faced (Ulbricht, 1952). While both Soviets and the Americans would continue to find social causes for youth crime; they would interpret them differently. The following cases illustrate how the East weaponized their explanations of youth crime to criticize their enemy’s socio-political system.

The 1953 protests and the events surrounding the Billy Halley concert, provide an entry point into how the East used youth crime to condemn capitalism and promote communism.

The 1953 Protests: Is Communism to Blame?

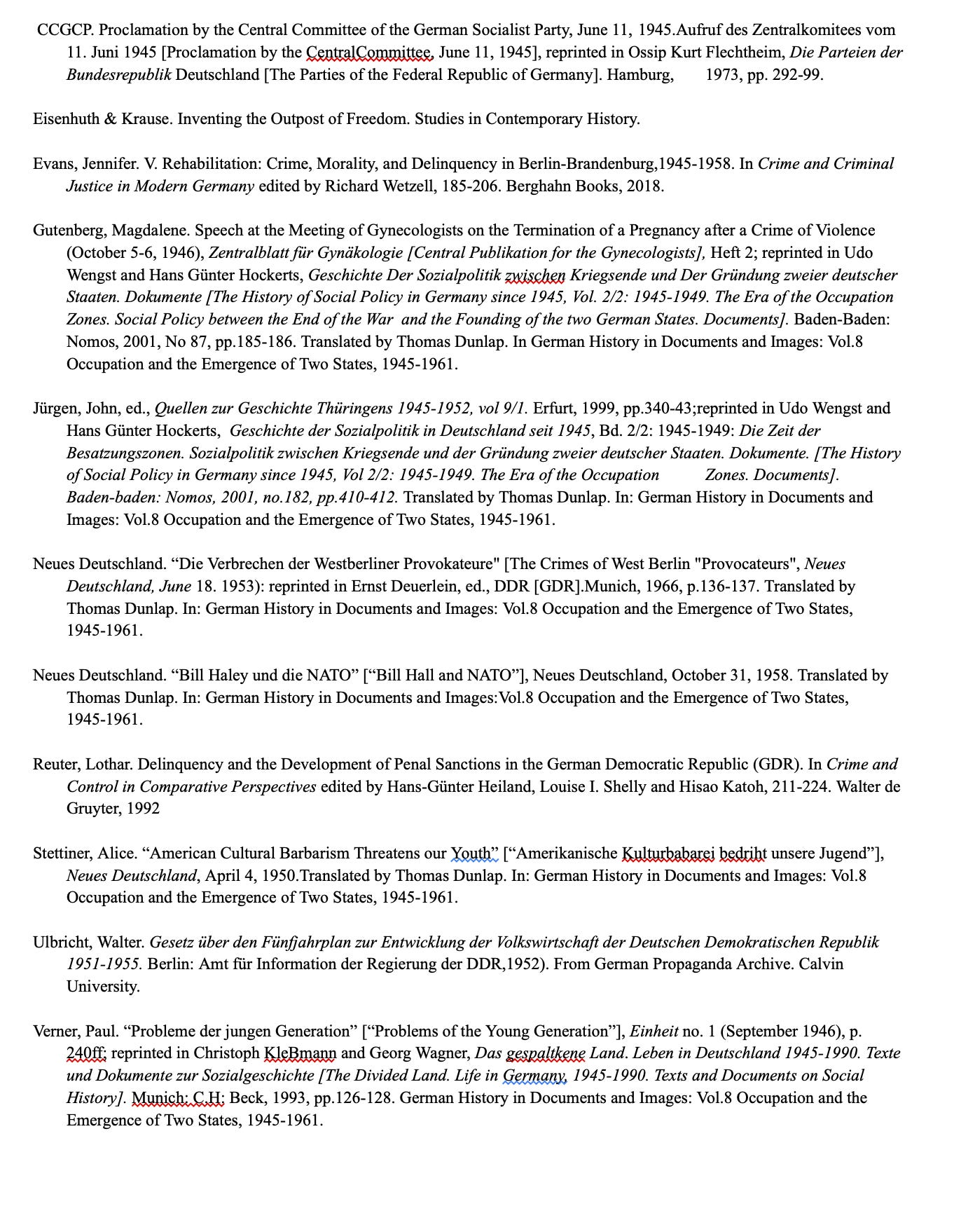

In 1953 there were large protests in East Berlin and East Germany. The protests show how the East sought to weaponize an internal crisis to figuratively punch the West. In the West, these riots were seen to reflect the dire living conditions and the increasing work demands workers had to meet in the East (Smith, 2024). In contrast, the East blamed the West. These protests also help understand how the East accounted for those crimes (Notizbuch, 1953).

The Eastern rhetoric around these protests echoes the German Committee’s declaration, and the party statement written by Verner. All three provide exemplar Eastern explanations for undesirable behaviors. All three blamed capitalism, and highlighted the importance of social conditions. Eastern accounts weaponized these events to criticize the West. East German authorities argued that the protests were the work of Western provocateurs.

This linkage was used to accomplish two objectives.

First, they could allay their government of responsibility because it was not the social conditions in their land that gave rise to rioting. The rioting, they claimed, was the work of Western agents.

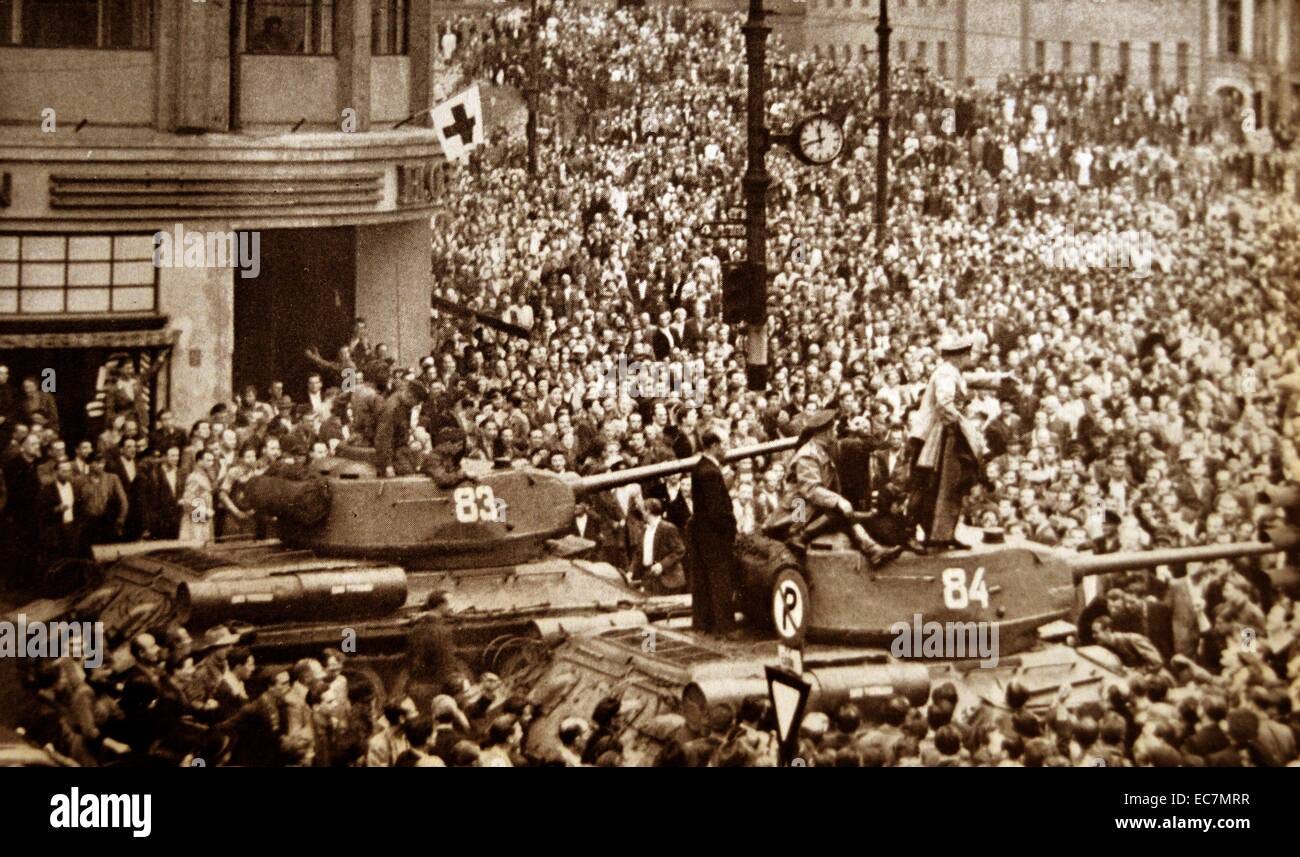

Secondly, they could claim that their system is superior because of the types of people it generates.

By emphasizing environmental factors (West Berlin provocateurs), East Germany could distance herself from the accusation of crimes stemming from social conditions in the East. Eight years had passed since the defeat of the Nazis, and thus the current social upheaval could not be linked to that environment. The Eastern account of the 1953 protests, blamed the West and the values it engendered for the riots so that it could exonerate ordinary life in East Berlin.

The official line was that protests were the result of Western “provocateurs” who had infiltrated the East (Notizbuch, 1953). The Eastern authorities linked the protests to an orchestrated campaign deployed through RIAS (Western radio service) (Eisenhuth & Krause, 2014). Given the stress that East German authorities had placed on the environment as a cause of crime, East German authorities needed to find a different culprit.

The story they concocted was that it was not the social, political, or economic conditions that caused people to riot, but the actions of Western saboteurs. They claimed that crime had social causes and having been in power for eight years they were responsible for creating the social conditions in East Berlin at the time the riots occurred. If there were no provocateurs involved, then East German authorities would have to assume responsibility for these riots.

The claim that Western provocateurs caused the 1953 riots in East Berlin allowed Eastern authorities to continue to link the environment with criminal tendencies and suggest that their system was superior because it did not give rise to rioters or saboteurs. An article in the official Newspaper, Neues Deutschland, contrasted the role of “Western provocateurs” who took action against the people’s protests and the people who “distanced themselves” from those actions (Neues Deutschland WB, 1953).

Unlike the saboteurs, the paper claimed that workers distanced themselves from the events and did not attack the people’s property (Notizbuch, 1953). Neues Deutschland added that the people “distanced itself from the provocateurs and their criminal acts” (Neues Deutschland WB, 1953). According to this view, even if some East Germans participated, they did so only because they were agitated, lured, and misled by Western actors. Thus, without making an explicit case, Eastern authorities could claim that the Western system breeds the kind of people who would destroy property and who would act as provocateurs.

In contrast, the articles implied that the East generates the kinds of people who distance themselves from violence, chaos, and crime. These people are trusting, which is why they can be misled by what they saw as corrupted capitalists. East German authorities would continue to stress the role of the environment in shaping behavior, and they would continue to sustain that capitalist environments engender undesirable traits. The same system that had caused Germans to follow “a false path, the wrong track, one that led to guilt and shame, war and ruin” when they supported Hitler, was now causing them to agitate the socialist East (Proclamation, 1945). In some ways the use of “provocateurs” in contrast to the use of people or workers when referring to those who participated in the riots, dehumanized them. This argument was an attempt to weaponize this crisis to attack the West.

The target of these riots is also connected to the differences between the East and the West. The protestors were said to have carried out “devious armed attacks on the People’s Police” (Neues Deutschland WB, 1953). The use of people’s policies demonstrate an effort to make the police appear to be for the people and of the people. This stresses the idea that the people would not attack their own police force nor the apparatus of a State that protects their interests. The choice of target being the institution in charge of securing Berliners can also be seen to imply something about the motivation of the rioters. The Eastern authorities emphasized that it was the “people’s” property that had been attacked and destroyed. This encouraged readers to think what kinds of people would destroy these and to what end? The East would continue seizing on opportunities to highlight differences and condemn capitalism.

Billy Halley and How the East Learn to Love Americana

East German authorities sought to weaponize social unrest to highlight the difference between communism and capitalism to try and win hearts and minds. The discourse about the protests that erupted at the Billy Halley concert in 1958, show both how youth crime was understood in the East and how these understandings were used to criticize the West.

The mayhem that occurred after the concert involved youth protestors who caused property damages. The East used these protests to denounce the West and what they claimed was an American conspiracy to prepare young people for thermonuclear war through the use of the media to degrade morals (Neues Deutschland, 1958). The impact of the environment could even be seen by how music and art affected people. An article on Neues Deutschland described the “dehumanizing effect of anti-music” as evident in the “damage and injuries” that these protestors caused (Neues Deutschland, 1958). The music is said to be dehumanizing and therefore dangerous even if it has nothing to do with war. The article laments how young people in the land of “Bach and Beethoven” listened to “anti-music” and it turned them into “raging beasts” (Neues Deutschland, 1958). The comparison between “anti-music” and “Bach and Beethoven” suggests a belief that one is cultured, and the other is not. The articles imply that Bach and Beethoven do not drive people to destroy property, but anti-music does. The one has value whereas the latter is vacuous and only generates money, disruption, and corruption.

The condemnation of the effects of American popular music is likely a way to address problems within East Germany. The focus on the destruction of property may have little to do with these specific protests and reveal an internal fight against such behavior. In 1958, the East documented 11,545 offenses against social property (Reuter, 1992). The focus on the destruction in the West then shows that this is not an Eastern problem, but a German problem (perhaps, a problem inherent to man). The Eastern authorities are also aware that East Germans are consuming Western media and linking the riots after Billy Halley’s concert is a way to delineate a connection between certain kinds of culture and youthful rebellion and rioting. This raised the possibility that the crimes against property happening in the East may have been caused by Easterners consuming Western media. The efforts to link criminal behavior to Western music may have been a way to try and divert attention from other plausible explanations for those eleven thousand offenses against property.

Similarly to the discourse regarding the 1953 protests East German authorities used the events after the Billy Halley concert to condemn the kinds of people the Western environment produced. This music is said to be dangerous because it attacks what is at the very core of their system: social property. That kind of anti-music is condemned by another newspaper because it exploits music as a means to rob people of their “dignity” (Neues Deutschland, 1958). The condemnation of the music is a proxy to condemn American culture and what the Soviets perceive to be the dangers of capitalism; namely, the subrogation of what is in the group’s best interest to the individual’s immediate pleasure.

This criticism of anti-music Billy Halley, and its effect on how young people act also reveal a conviction that media not only shapes how people see and interpret events, but more importantly how they act. Secondly, the underlying assumptions about the effects on culture on behavior reveal an apathy to American music and imply that American culture is beastly. The article draws a causal link between political ideology and music, “the anti-human policy of atomic war and the anti-humanistic stultification of rock ’n’ roll grown from the same root. This is no coincidence”(Neues Deutschland, 1958).

The connection with atomic war is likely an attempt to raise the stakes about the possibly negative effects of American culture. It is a rhetorical device to remind readers that the stakes are too high, and one should not risk it. As in other condemnations, East Germans draw a parallel with Nazism. The article claimed,

“Hitler had his methods to make the German youth ripe for Fascist war crimes” and the Americans have theirs (Neues Deutschland, 1958).

For them, it was simple, the behaviors that American culture is alleged to engender demonstrate that the American worldview is devoid of “ideals that are worth working, fighting, and living for” (Neues Deutschland, 1958). This criticism sustained that the problem with capitalism is foundational in that it sacrifices everything of value for profit or immediate pleasure. In contrast, they claim to offer a system that places the interests of workers at the forefront, a system composed of structures that does not generate provocateurs, rioters, and greed.

Halbstarke

The East responded differently to this halbstarke phenomenon which it at first tolerated, but then denounced. The East would struggle with how to best understand this phenomenon. Some would argue that the Halbstarke were the embodiment of fascism whereas others would applaud them for resisting the West and rearmament (Poiger, 2009).

By 1956 East Germans stopped accommodating Halbstarken “styles and increasingly reverted to earlier attacks that labeled youth German rebels and American popular culture fascist” (Poiger, 2009) This change is probably due to the linkage between these ways of dressing and American culture. Further, the powers in the East had linked the consumption of American media to a host of problems and thereby had to also condemn this movement because it was inspired by American media.

Conclusions

East German authorities used these events to stress the importance of the cultural environment in shaping behavior and claimed that Western culture produces undesirable dispositions.

In short, the Eastern response to American music, and American film was to denounce them and call for “better books” and better options for the young (Stettiner, 1950). The manner in which East German officials explained crimes and criminal activity allowed them to criticize the West and highlight the alleged superiority of their system.

This foray into East German criminology during the Cold War hints that socio-political worldviews significantly impact how States explain events and how these explanations shape the kinds of solutions they offer.

This post heavily draws from an essay Christian wrote for a class on the history of everyday life in Cold War Berlin. Christian would like to express his gratitude to Briana and Caroline for an exciting course, their help and support. Lucas and Christian have worked on a substantial revision of Christian’s original work.

Sources