Youth Crime, Capitalism and Why Communism Sucks

Factors Connected to Crime Are Much Worse in the East

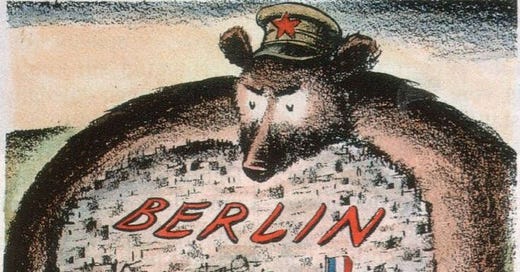

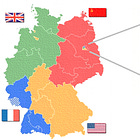

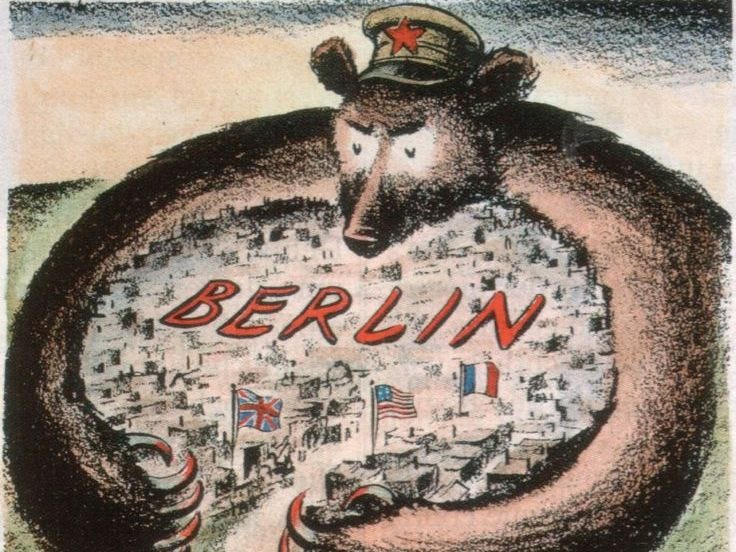

The defeat of Nazi Germany left the nation in disarray. Life got worse for ordinary Germans. Crime continued to increase. Growing tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States transformed Berlin and Germany into an arena where the fruits of capitalism would be compared to those of communism. In West Germany, criminologists developed theories which allowed them to distinguish their ideas from the Nazi past. The kinds of explanations they offered highlighted the alleged superiority of their political system (capitalism). In the West, crime was often linked to the economic German context that resulted from the war. Jennifer Evans, a historian, said that for them, the “soaring level of criminality reflected the war-ravaged conditions into which the younger generation had been born.” (Evans, 305)

West German thinkers argued that some crime was to be expected given the destruction of German industries and infrastructure. During the war, many Germans died, cities and structures were destroyed, and a generation that had been brainwashed with Nazi ideology was liberated. Specialists in the West argued that the increasing crime rates resulted from Hitlerism and the devastation caused by the war. This understanding of why crime increased, determined the kinds of solutions they proposed.

Solving Problems Through Capitalism

These solutions were concordant with a capitalist / market system. First, Western professionals pushed capitalism because this system would repair the loss in infrastructure, promote innovation, employment, and thus solve these issues. For example, in 1948 they introduced a new currency and helped establish markets. This move angered the Soviets so much that it led to the infamous Berlin Blockade. This currency quickly dissipated the black market in Berlin as shelves once again had products to sell. In short, the introduction of a new and stable currency was meant to unleash the market to solve issues which in turn would reduce criminal activity. Secondly, there was a marked shift in how the United States spoke about West Germans. Unlike the initial American policy that trained soldiers to be wary about Germans; now West Germans were depicted as heroes defending democracy and freedom in the front lines (Reuter, 214; Poiger). This second shift also fits with this idea of a free, open society, with mostly open markets.

The significance of Germany and Berlin, made the reduction of crime one of the main concerns for American and West German leaders. Criminologists and jurists debated whether the purpose of criminal justice was retribution or rehabilitation (Godecke, 284). Soon, the Official Committee on Criminal Law (1954-1959) supported a retributive approach and kept penal punishments (Godecke, 288). Petra Gödecke, a German historian, argued that the retributory approach won because it conveyed a greater sense of security (290). She also suggested this allowed academics to discuss the purpose of punishment without having to deal with how it's put into action. The commission recognized that current penalties for small crimes resulted in overcrowding of prisons. Rather than solving the problem, they only changed how these people were categorized (from gefängnis strafen to Strafhaft) (Godecke, 288). In short, the West German state kept many of the Nazi penal codes. Another issue had to do with youth crime and young people engaging in problematic behaviors.

Is the West Rotten? The Halbstarke Phenomenon

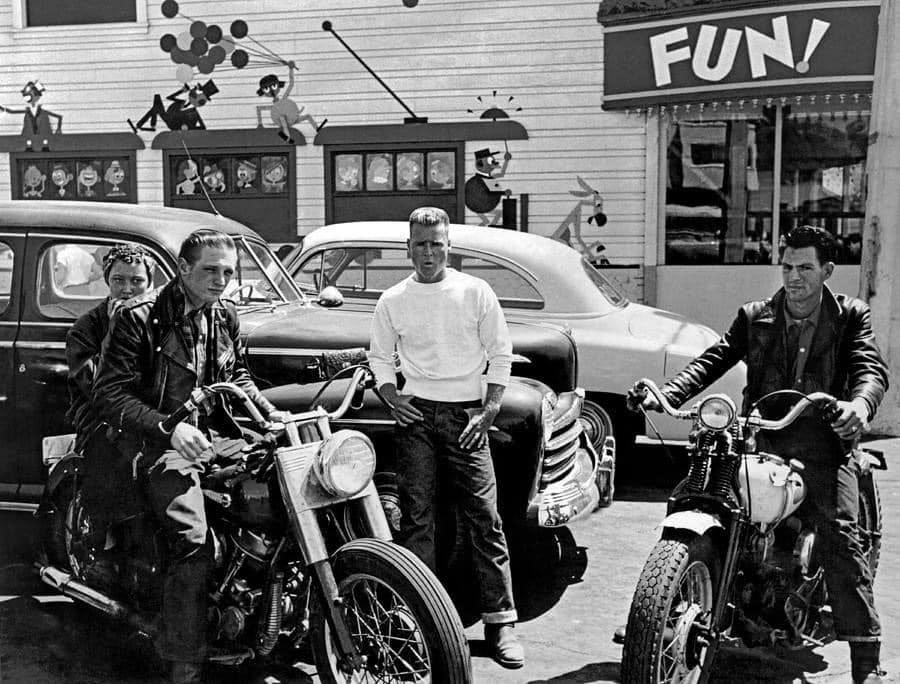

In West Germany, youth crime and undesired behaviors were explained in such a way that they reaffirmed capitalistic values in contrast with the communists in the East. One of the major challenges in the West was the Halbstarke. The Halbstarke refers to an adolescent subculture mostly of working class men who wore a quiff, jeans, and leather jackets, and behaved in aggressive and provocative ways. They drew inspiration from American movies like Rebel Without a Cause. These young people often spent time outside, listened to rock music, and engaged in rioting.

The situation in West Berlin troubled many, as there were at least thirty six riots between April and September 1956 in West Berlin, and the Halbstarke often participated (Poiger, 79). These protests were linked to American popular culture in both East and West Berlin (Poiger 71). The Halbstarke were perceived as a threat because they questioned the new kinds of German men envisioned by West German authorities. This gained importance because when relations between the US and the Soviets soured, a decision was made to rearm Germany despite an agreement, made at the end of the war, that Germany would never rearm. The riots and the Halbstarke figuratively challenged the economic and political system’s ability to maintain order and to foment a healthy society. West Germany had sought to develop a new prototype of their ideal soldier: a brave and obedient man who was first a citizen in uniform; a citizen that also was a husband, and a father (Poiger, 73-74). This new cultural paradigm threatened many established ideas about good citizenry.

The Young Have Needs Which Capitalism is Better at Meeting than Communism

West German commentators agreed that the Halbstarke worried them, even if they disagreed over the particular significance of this specific group. Heinz Kluth, a sociologist, argued that the Halbstarke was limited to a small portion of the youth and thus not a significant worry (Kluth, 1956). He argued that the problem only seemed big if one considered law-abiding jazz goers, film lovers, and others part of the problem (Kluth, 1956). He thought that the fear of the Halbstarke resulted from the “condensation of all confusion, judgments, and prejudices into a single catchword” (Kluth, 1956). He observed that while the Halbstarke are nothing to worry about, the “extreme forms that their reactions take” and the existence of the movement reveals underlying issues that merit attention (Kluth, 1956). Importantly, these causes were not inherently produced by capitalism but rather by modernity. Instead, Kluth held that modernity and the city environment, disoriented youth who thus acted out (Kluth, 1956). Other thinkers like Adolf Busemann also thought that the young commit more crimes in the cities than in other settings (Busemann, 1956). These concerns about the city and its effect on behavior were broader.

Western efforts to explain the rise of the Halbstarke emphasized the role of culture but sought to ground these explanations in biology. Kluth explained the existence of the Halbstarke and their actions by drawing from physiology and focusing on its interaction with culture. According to Kluth, young people inherently have a sense of action, they experience a tension between the “urge to do something and be someone, on the one hand, and emotional-mental and social frailty, on the other.” (Kluth, 1956) Kluth argued that this urge to act grows stronger the more people are “squeezed into a pattern of rigid behavioral norms” which was the case after the war and is the case in cities (Kluth, 1956). This is a byproduct of modernity, but is not particular to capitalism. The perception in the West was that citizens in the East had even more prescribed and rigid behavior ways. Thus, without explicitly mentioning the East, Kluth observations highlight differences between these systems and imply that capitalism is better.

The changing demographic realities and the rise of cities concerned some thinkers because undesired behaviors appeared to be more prevalent in urban settings. Kluth thought that cities demanded more discipline by offering shorter, easier workdays that also required more discipline and thus exacerbated the tension all young people feel (Kluth, 1956). Once again, there is an implicit message about the East where factory work is more monotonous and regulated. He contended that this urge is nothing new and was not perceived to be a problem when its expression was aligned with the interests of the government, such as when it was channeled against the Jews during the Nazi regime (Kluth, 1956). Whereas now, the same behaviors worry people because there seems to be no motivation and there is no alignment between the behaviors and policy (Kluth, 1956). Further, the fact that these acts exist regardless of political system, exonerated capitalism. He stated that these actions are seen as a challenge because of an “unwritten law that the youth must be urged to be quiet” (Kluth, 1956). Kluth thought that young people have certain needs that are not being met. Consequently, meeting them would reduce undesired behaviors.

Kluth argued that young people need recognition and a supportive environment which many lack (Kluth, 1956). Cities are asking young people to be a “child at home, an adolescent within the scope of certain laws and the demand of recreation, and for the most part an adult in the world of work and professional life”(Kluth, 1956). This dissonance frustrates them and puts them in a place where they need to react. In quieter settings, their roles are more defined, and they have opportunities to take limited actions to quell this need. Cities also have many broken families which remove the support young people need to develop (Kluth, 1956). Likewise, the Minister of the Interior, Gerhard Schrörder, urged that young people needed better leisurely activities to keep them engaged (Poiger, 2009). This reasoning suggests that the war continues to account for some youth misbehavior because so many households lack fathers.

Moreover, Kluth’s analysis suggests that politicians need to think about how to better structure cities, and educational opportunities so that the young can develop fruitfully. Even if some of these reasons can be linked to a capitalistic organization it is vital to note that they are not inherently capitalistic. Thus, while these circumstances arose under a capitalist system, they are not necessarily part of such a system. Similarly, Hans Muchow, an education expert, spoke of a mix of primitive and biological causes that meant people could not go beyond certain stages before they developed fully (Poiger, 2009, p. 96). Muchow thought that American influence, working class upheaval, and the desire to take political actions contributed to people participating in these undesirable acts (Poiger, 2009).

Western critiques of youth crime and culture recognize that the world created by adults drove the young to commit crimes. However, both Abendroth and Kluth found that part of the youth problem can be attributed to the current state of the world and not inherent to the socio-political system. If anything, they thought communism exacerbated these problems.

The rise of Halbstarke made dealing with young people more important in West Germany (Abendroth). In 1956, Alfred Busemann, in the West, wrote a journal article regarding his concerns about the rising criminal tendencies among the youth, which is part of a larger phenomenon. He traced the origins to the 1920’s. Like Kluth and Abendroth, he also thought that the cities contribute to youth crime. Busemann also started from biological observations and according to him, Germans are reaching puberty at an earlier age. Busemann was shocked by the total amount of crime, and reports that in 1954 at least 560,000 people had to face a judge because of their actions. He made the astute observation that these are only the crimes that were reported and for which a person was charged, thus excludes unreported crimes as well the “immeasurably broad layer of behaviors…that lead in the direction of those crimes”. He was gravely concerned by what appears to be an intense wave of crimes.

Busemann worried about the effects the new social environments had on people. He argued that people have lost inhibitions and that tens of thousands “participated without being aware that they were committing outrageous crimes; not to mention the political murders in the narrower sense since 1918.” (Busemann, 1956). Like Abendroth, Busemann thought that a cultural change has made people more likely to commit crimes. Busemann wrote that “A dismantling is under way of the very inhibition that once allowed for the establishment of human civilized behavior; and without this inhibition, the peaceful coexistence of people is impossible, since respect for life and health, the gift commandment in the catechism: “Thou shalt not kill!” Is the very first prerequisite of all human culture”(Busemann, 1956). He argued that in its current state, civilized behavior is becoming impossible because the respect for life has eroded. This destruction of values is occurring, and he thought it could be arrested through socio political activities. In his view, youth crime is nothing but a “manifestation of this cultural decay.”(Busemann, 1956)

The barbarization has eroded the respect for other life that is foundational to communities with morality and law (Busemann, 1956) . Busemann advocated for an effort to educate the young even if teachers had to use “brute force” to “secure the peace”(Busemann, 1956). Like other Western commentators, he does not link these problems to capitalism. He called for strong “socio-political and socio-pedagocial activity” to end abuse of democracy.(Poiger, 2009) These activities would promote social relations and help restore respect for life and encourage the development of civilized behaviors.

Conclusions

These Western commentators argued that West Germans bore responsibility for creating a system in which crime proliferated and where young people were more likely to be drawn to a life of crime. Some thinkers thought certain cultural products exacerbated this issue. Nevertheless, they called for changes within the current system. They proposed solutions that would ameliorate this situation. Eventually, West German thinkers started to find other links, and would increasingly “depoliticize both American imports and Halbstarke behavior.” (Poiger, 2009) This shift to other causes of criminality and undesired behavior would also focus on social causes.

What is interesting for our purposes is that most of the factors that they identified would have an even worse effect on the East. Further, some of the solutions they posed could only be implemented in the West. Thus, while these Western commentators did not address the East, their ideas implied that capitalism is a better system than communism. Thus, West German approaches to crime, criminality, and youth crime were part of a cultural Cold War by which the West sought to demonstrate the absolute superiority of its socio-political systems.

This post heavily draws from an essay Christian wrote for a class on the history of everyday life in Cold War Berlin. Christian would like to express his gratitude to Briana and Caroline for an exciting course, their help and support. Lucas and Christian have worked on a substantial revision of Christian’s original work.

If you liked this story and want to learn about Crime in East Berlin Please See

A discussion of how East German Criminologists Claimed Capitalism made people worse

East German Criminology Linked Fascism, Capitalism, and Crime

The terrible condition in which Berlin found itself after the war

Ideas about Crime in Weimar Germany and Nazi Germany